I’ve sort of fallen off here and broken my rule of sending something out once a month… But truly I can hardly even remember the last two months of my life. I let time wash over me as my days merged and dismembered from my body and those around me. I ate loads and then not much at all. I got cold sores and sore throats. I hid from the rain.

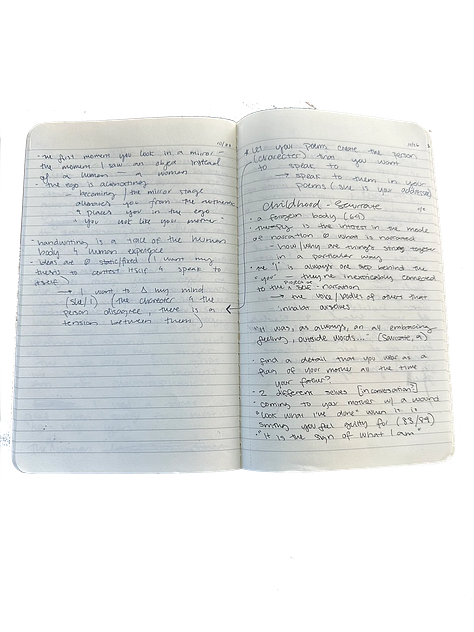

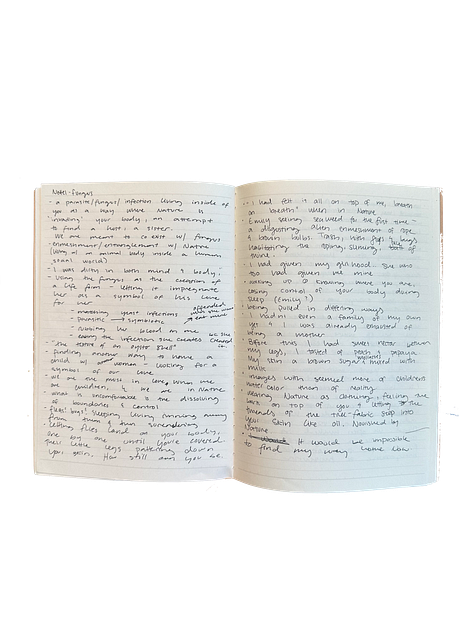

I’ve been thinking a lot about fragments over the last year. How narratives and stories are told through broken images. The idea of the archive and creating an ethnography. I’ve been thinking about the archives of my life: my memory, notebooks and journals, personal poetry, boxes tucked under my bed, and oral familial histories. I’ve been thinking about stories that live in your body but are not entirely your own—what is one supposed to do with those stories anyway? When you are in the womb of a body that is feeling and experiencing, are those feelings and experiences not also shared and passed down to you?

I turned in my thesis a week and a half ago and titled it Becoming A Body of One’s Own. It’s a collection that asks a lot of these questions, or, at the very least, these are some of the questions that I thought about while writing it. At the core, it is a project on self-narration. It explores what constructs a self and the ways in which self-narration is written. Specifically asking, what creates an intersectional identity and how is it best written? To do this, much of my thesis is about fragmentation and using a hybrid form to challenge and subvert traditional literary forms in hopes of getting closer to a fragmented and intersectional identity like my own.

I found that a fragmented form mimics the idea of the archive that I was so stuck on and that the fragments themselves entangled and created a new kind of connected mycelium that also seemed present in selfhood. Everything is connected. Everything is fragmented. That is how my own identity and selfhood felt and so that was the little voice singing around my writing and collection: Everything is connected. Everything is fragmented.

Unfortunately, since my thesis work and my personal life became the same project, I have only thought about this one project in the last two months. So to make up for my absence from this newsletter, I thought I’d construct a little collage of written fragments I’ve collected over the last two months—much of it on the theme of fragmentation in my thesis and one little excerpt from something I drafted in March.

Inside my pencil case is a piece of lined paper folded over and taped a few times until it became an envelope. My makeshift envelope has traveled with me since December—a night I cried myself to sleep and awoke at 2 am to write down 13 wishes for the new year. I had intentions of a ritual. I would blindly burn one wish each night on the correct days that lined up with the new moon. I would give all but one wish to be granted by the universe while that single wish would be up to me to actualize. But days passed and I never burned any wishes. I continued on the way I have been: moving and moving, laying paralyzed by movement, and then moving again, an object in motion with no obstruction in sight. Now, 13 forgotten wishes live in my bag and I am too superstitious to remove them or look at them or really to touch them at all, so they stay put, and the desire for a better year tugs at me each time I dig for a pen.

You would not know this because I hardly write to you with any sincerity these days, but in December, I had big plans to begin my life again this year. Though I do not remember the exact 13 wishes I wrote down, I know they all longed for some kind of life and existence to begin again.

One year ago I marked time by sight rather than date. I saw color again and so I knew time had passed and I was no longer living in grey dreadory. I considered my ability to see details and color a sign that my life was returning to order and stability. I wished to come alive inside of myself again, to possess autonomy, and to consider the future as something other than a need for the past. Somehow a year passed and I loved and I saw color but I never quite felt alive like I had imagined. I kept waiting…

Fragment 23 (the final piece) from Becoming a Body of One’s Own:

Notes of a Childhood1

Brown picket fence. Nana (my dog) barks at strange men who pass. We can’t afford a babysitter.

Swim lessons with Daddy, I eat pistachios for the first time. I am too afraid to go swimming.

Liz makes us popcorn with Skittles. Liz rubs my back until I fall asleep. I know love and safety.

Melanie knocks on my window to come and play.

Joe jumps over the brown picket fence and tears his pants. Joe teaches me how to write and homeschools me. Joe eats playdough to please me. Joe throws me in the air and makes me laugh.

All of my pee on the tile. I want to know what Roman feels so I pee standing up.

Daddy transcribes my first journal entry for me. I am three years old.

The radiator I climb onto and swing from the vines in our backyard.

The young girl who lives in the apartment behind us is raped in the middle of the night. Mama and Daddy tell me at the foot of my bed. Safety is fickle, brittle even.

Pan dulce at Joe’s dads funeral. Cousins I do not like or know well. Live music. Joe sings.

The earthquake of ‘06. Mama is at work. Daddy and I under the doorframe. I am beginning to understand fear.

All of the water up my nose: surfing with Mama, the beach with Mama. Sleeping on my side to get excess water out of my ear.

Grandma's sad brown couch. I get a single scoop of ice cream with Grandma at the 7-Eleven by her apartment even though she always promises me a double.

Spitting in Nikolai’s face.

Writing stories where I am an orphan and my parents have died in tragic ways.

Journals begin to fill.

All the lies I told.

Sage’s two moms. I ask my dad when he will leave and I will get two moms.

The Mexican corner store near my house. I eat de la Rosa Mazapan often.

Daddy and I walk Nana and I see a woman drunk for the first time. Her face and eyes are red, her words and walk are slurred. Daddy holds Nana and I close.

My Grandfather yells at Roman. We leave Christmas early.

Roman’s broken DS. I snap it in half. I cannot process that it is an item outside of my imagined world.

Mama comes home with a brand-new fancy car. We all look at the shiny functions. Change is beginning.

Everything I stole.

Lunch in the art room at school. I do not have many friends.

Joe leaves. He is an addict. Liz tells me crying at the In N Out in Eagle Rock.

Lice. Four times. Grandma gets it out of my hair twice.

The plane ride that almost kills us. Mama tells me to pray for the first time. She says we need to pray to every God in every religion, just to make sure we don’t miss one.

Moving out of our small home and into the foothills. I am afraid of heights. I cry for years.

All of my pee in the grass. I want to know what Violet (my dog) feels.

Sewing my first stitch.

Making a doll.

Mama stops talking to my grandfather. She laughs and tells us he is her sister’s father, not hers.

The Mexican restaurant bathroom where I bleed for the first time. Mama bakes a red velvet cake.

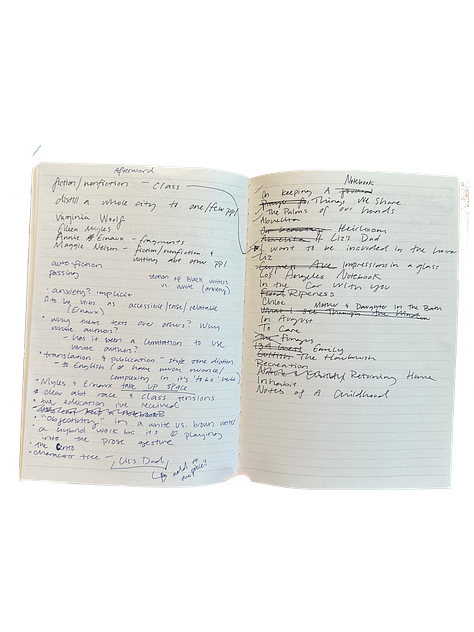

Section 1 of the afterword, edited down for the sake of this newsletter:

On The Notebook & Self-Narration:

Notebook (1981)

I was so willing to pull a page out of my notebook, a day, several bright days and live them as if I was only alive, thirsty, timeless, young enough, to do this one more time, to dare to have nothing so much to lose and to feel that potential dying of the self in the light as the only thing I thought that was spiritual, possible and because I had no other way to call that mind, I called it poetry, but it was flesh and time and bread and friends frightened and free enough to want to have another day that way, tear another page.- Eileen Myles

The notebook, according to Myles, is a channel into the mind of poetry. Into life in the quotidian and the dramatic: the spiritual, the bread, and the friends frightened and free. To write in the notebook is to memorialize each of these moments without the pressure of objectivity. That is where the true honesty of the notebook is found: in the freedom from objectivity and the emphasis on the moment itself, its lived experience, and the psychological affect of that experience on the body and self. Perhaps that is where the notebook becomes the mind of the poet, it is the evidence of a life lived, distilled into fragmented images to find the honest sensation, the very core.

This collection opens with a piece about the practice of keeping a notebook. It is critical to my mind for the very reasons Myles posits and thus is critical to my thesis. The notebook distills writing to me, it brittles it down to the essence of it all: memory and communication, keepsakes of language and time. It is a practice of noticing, taking a catalog of the quotidian and the life that builds the self. Evidence of a life lived.

In Joan Didion’s “On Keeping a Notebook”, which my opening piece was partly inspired by, she writes, “It all comes back. [...] We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were. I have already lost touch with a couple of people I used to be.” Interested in the self through memory, Didion uses the notebook to collect memories and re-construct past selves. She speaks of the self as an accumulation of various collectibles, people to “keep in touch with”. Not books put away on the shelf to rest and forget, but small flames still burning, mild in their glow but active nevertheless, their quiet burning remains hidden somewhere in the present body.

The notebook is a space for communication with oneself. Though many say a notebook must exclude an audience, I find that to be nearly impossible to accomplish. The speaker and the addressee of a notebook often begin as the same person, whether that is the author of the present, future, or past self, it is a version of the self nonetheless. The notebook is a conversation between the various small flames, the many versions of selves, Making the notebook a practice of creating the self through the recovery of the past and vice versa.

As Didion and Myles explore, by keeping quotidian memory in notebooks, no matter how mundane, there is tangible proof of a life lived; of a person on the other side of the page. A history is created and recreated within the page. And it was here that the notebook became my access into the genre of self-narration with the most truth and honesty—most typically, honesty before truth.

While the notebook is a communication between the author as both the speaker and the addressee, it can be seen as an extension of a private space. A private space that can be stepped into at any moment, no matter the broader location: in a café, museum, bedroom, park, etc. I believe it is in this private space where honesty is truly found. Throughout my time writing my thesis, I considered the difference between honesty and truth. As much of the content of my thesis consists of family stories and memories that are not my own but were told to me throughout my life, I was constantly running into the failures and disappointments of changing human memory. These were not stories that had been preserved in their truth or fact, they were told through perspectives hurt and confused and then retold through me, a narrator who is certainly not omniscient or all-knowing. They are stories, at the end of the day, they are fiction in many ways.

There have existed many times when I reminded my mother of a story she once told me as a child—a story I held onto and revisited often---that she no longer remembered and swore had never occurred. Several weeks, months, or years later, my mother would come to me re-telling that very story as a memory she had “just unlocked”. Trauma is a complicated phenomenon in the brain and my thesis has never attempted to hold the women in my family to a standard of truth; I simply do not find it to be what is interesting in these stories. My thesis is interested in the honesty of emotion and the psychological affect of lived experiences. I’d like to think of my writing in this collection as an opportunity for the women in my family to write in their own notebooks. Scribbling fragmented words and images of time past, vague sentiments that I have collected and strung together over the years. It brings me joy to consider that I have let my mother, aunt, and grandmother lead the pen in my hand so that they could be frank and honest about their stories, their fiction, and their lived experiences through me.

Rather than emphasizing truth, my thesis incorporates fragments of fiction and nonfiction in an attempt to understand emotion and mental disarray honestly. In this way, the notebook became a philosophy about honesty that I carried with me throughout my thesis. It was where I could explore the idea of selfhood without judgment and pressure to adhere to genres, such as fiction and nonfiction, or moral arguments, such as lying and truth-telling.

As I explored selfhood through the eyes and stories of others, I confronted my entanglement with the women in my life: my mother, my grandmother, my aunt, my queer relationship, and my homoerotic friendships. I needed to find out how I was going to be the tying thread in this collection. How was this going to be a piece exploring self-narration? For me, the answer was in utilizing the notebook as a form itself.

The notebook form is used several times throughout the collection, explicitly in a few pieces but also inexplicitly in terms of fragmentation, hybridity, and freedom to write and create honestly as one might in one’s personal notebook. This form is applied in “Los Angeles Notebook”, “Notes of a Childhood”, and “Returning Home” in varying degrees. These pieces provide a wide range of context to the speaker’s life and internal world while never deeply analyzing the memory. In particular, “Notes of a Childhood” feels as though the speaker is attempting to remember everything she can from her childhood, at times almost clinically or journalistically; consisting of much shorter lines that are truly note-like but do not adhere to numbers. These pieces create impressions, gestures, and glimmers of time past while the form relies on the reader to imagine broader images and narratives without conclusions. In turn, it allowed me as the writer to create order and disorder for the reader to sort through like an archival journal. True sketches of being, these pieces stand as rough outlines to contrast the more developed sketches and drawings in the rest of the collection.

Thinking of the self, as well as this collection, as various transparent films layered on top of each other seemed to be the most honest approach to the intricacies of selfhood and the intersectionality of my particular identity and positionality.

My thesis will be accessible at some point soon… It will live in Reed’s digital archive for those of you with a Reed login. But I’m not sure how I want to share/publish it further than that right now, so stay posted!

After Susan Sontag’s “Notes of a Childhood” from Reborn (Journals and Notebooks, 1947-1963).

This was so good and insightful thank you!